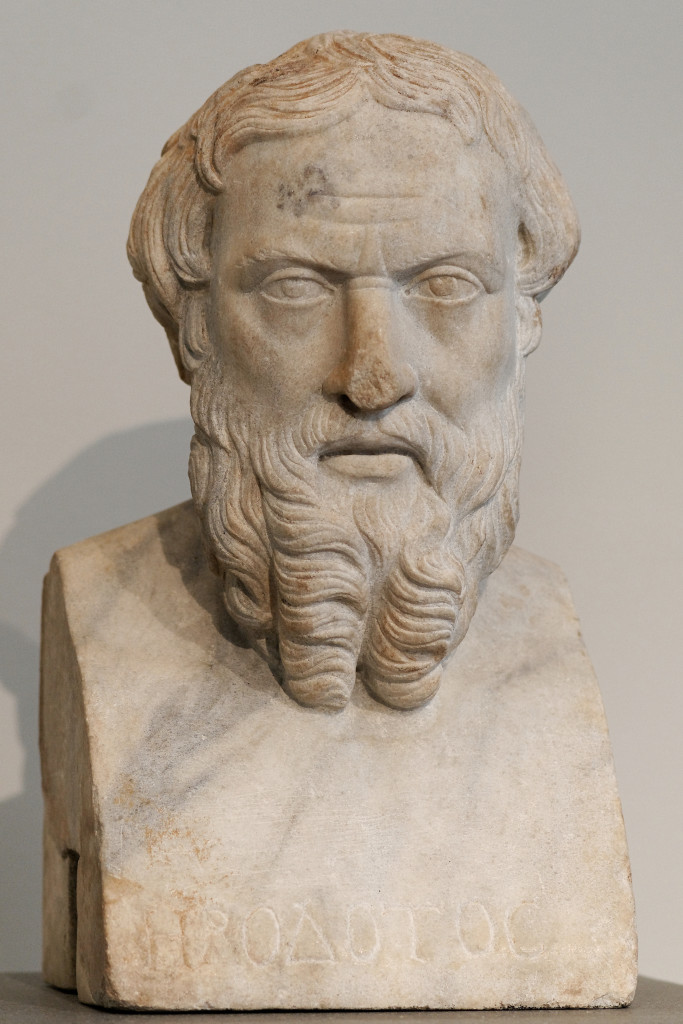

Marble herm of Herodotos with Greek inscription. Roman copy of the Imperial era (AD 2nd century) after a Greek bronze original of the first half of the 4th century BC. From Benha (ancient Athribis), Lower Egypt. It is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The photo was taken by Marie-Lan Nguyen and is distributed under a CC-BY 2.5 license.

Inessential knowledge can be a source of true delight. That is what Bertrand Russell had in mind when he wrote of the acquisition of knowledge that does not contribute to professional competence as “a means of creating a broad and humane outlook on life.” Any person sharing his habit of mind will be well launched on the reading of Herodotus — for Herodotus aimed to both inform and delight his audience in writing the story of how a small and internally divided jumble of Greek city states united to repel two successive invasions by the mighty Persian Empire. This narrative, which forms the core part of his work, has always been deemed essential to any good history curriculum and in more recent times it has proliferated into popular culture via the medium of the Hollywood blockbuster film. Thus knowledge that the Greeks scored a decisive naval victory over Xerxes at the Battle of Salamis, and that this was somehow important for shaping the future of Western civilisation, is just as likely to be found among the learned as it is among couch potatoes. But in spite of these efforts on the part of our cultural guardians, consider for a moment how many among us pass through life wholly unaware that Xerxes halted the advance of his entire army on the road to Sardis just to decorate a tree. Herodotus virtually revels in pleasant anecdotal knowledge of this kind. It is this sort of inessential knowledge that is my focus in the present post. In what follows, I have arranged Herodotus’ most noteworthy digressions according to the nine books of The Histories, which are traditionally named after the nine Muses. In the fullness of time I aim to accompany each of these stories with a blog post.

Book I: Cleo

-

In Defence of King Candaules (1.8–1.13)

This Candaules, then, fell in love with his own wife, so much so that he believed her to be by far the most beautiful woman in the world; and believing this, he praised her beauty beyond measure to Gyges son of Dascylus, who was his favorite among his bodyguard; for it was to Gyges that he entrusted all his most important secrets. After a little while, Candaules, doomed to misfortune, spoke to Gyges thus: “Gyges, I do not think that you believe what I say about the beauty of my wife; men trust their ears less than their eyes: so you must see her naked.”

- Cleobis and Biton: The World’s Second Happiest Men (1.29–1.33)

- King Croesus and the Oracle of Delphi (1.53)

- Thales Predicts the Solar Eclipse of May 28, 585 B.C. (1.74)

- Astyages Tricks Harpagus into Eating his Son at Ghastly Feast (1.106–1.130)

- The Tomb of Nicocris (1.187)

Book II: Euterpe

- Expedition into the Heart of Africa (2.32–2.33)

-

Herodotus on How to Catch a Nile Crocodile (2.70).

They bait a hook with a chine of pork and let it float out into midstream, and at the same time, standing on the bank, take a live pig and beat it. The crocodile, hearing the squeals, makes a rush toward it, encounters the bait, gulps it down, and is hauled out of the water. The first thing the huntsman does when he has got the beast on land is to plaster its eyes with mud; this done, it is dispatched easily enough – but without this precaution it will give a lot of trouble.

- The Treasure-House of Rhampsinitus (2.121a–2.121f)

-

Philitis and the Great Pyramid (2.124–2.128)

Thus, they reckon that for a hundred and six years Egypt was in great misery and the temples so long shut were never opened. The people hate the memory of these two kings so much that they do not much wish to name them, and call the pyramids after the shepherd Philitis, who then pastured his flocks in this place.

- The Herodotus Machine (2.125)

- King Amasis and the Golden Washbowl (2.172)

Book III: Thalia

-

The Table of the Sun (3.17–3.25)

Now the Table of the Sun is said to be something of this kind: there is a meadow outside the city, filled with the boiled flesh of all four-footed things; here during the night the men of authority among the townsmen are careful to set out the meat, and all day whoever wishes comes and feasts on it. These meats, say the people of the country, are ever produced by the earth of itself. Such is the story of the Sun’s Table.

- The Travels of Democedes of Croton (3.125)

- Syloson and the Flame-Coloured Cloak (3.139–3.149)

Book IV: Melpomene

-

How to Make Kumis the Scythian Way (4.2)

The Scythians insert a tube made of bone and shaped like a flute into the mare’s anus, and blow; and while one blows, another milks They make the blind men stand around in a circle, and then pour the milk into wooden casks and stir it; the part which rises to the top is skimmed off, and considered the best; what remains is not supposed to be good…

- The Lost Poem of Aristeas (4.13)

- The War on the South Wind (4.173)

- The Peculiar Customs of the Ataranteans (4.184)

Book V: Terpsichore

- The Olive Wood Statues of Epidarus (5.82–5.88)

- The Coded Message of Thrasybulus to Periander (5.92f)

Book VI: Erato

Book VII: Polymnia

- Pythius makes an Unreasonable Request to Xerxes (7.27–2.29, 7.38–2.40)

- Pharnuches Tossed from his Horse (7.88)

- The Execution of Leon by the Persians (7.180)

- Ameinocles’ Lucky Day (7.190)

- Aristodemus (7.229–7.231)

Book VIII: Urania

- Scyllias the Diver (8.8)

- The Persian Royal Mail Must Go Through (8.98)

- Hermotimus Takes Revenge against Panionius (8.106)

Book IX: Calliope

Scattered

- The Xerxes You Didn’t Know

- Xerxes’ Dream (7.12–7.20)

- Xerxes Angered by Pythius’ Request (7.27–2.29, 7.38–2.40)

- Xerxes Decorates a Tree on the Road to Sardis (7.31)

- Xerxes Sentences the Hellespont to 300 Lashes (7.35–7.54)

- Xerxes Hankers to Watch a Rowing Match (7.44)

- Xerxes Reflects on the Shortness of Life (7.45–7.46)

- Xerxes Presents the People of Acanthus with a Suit of Median Clothes (7.116)

- A Trio of Mythological Animals

- The Flying Snakes of Arabia (2.75)

- The Gold Digging Ants (3.102)

- The Cinnamon Birds of Arabia (3.111)

- Various Marvels

References

[1] The Histories by Herodotus; translated by A. D. Godley (1920), Harvard University Press. The full text of this edition is available online at The Perseus Project.

[2] ‘Useless’ Knowledge by Bertrand Russell (1935).

[3] 300 directed by Zack Snyder (2006).

[4] 300: Rise of an Empire directed by Noam Murro (2014).